Too many children with vision disorders have unmet needs for care, leaving them vulnerable to negative effects on learning and development. Racial and socioeconomic inequities in access to care are evident across a variety of measures and studies. White children and children from families with higher incomes are more likely than other children to have diagnosed eye or vision disorders, suggesting greater access to diagnostic eye care. Meanwhile, among children with diagnosed eye conditions, black children have lower overall health care expenditures than white children, but twice the expenditures for eye/visionrelated emergency services, possibly indicating less access to a regular source of office-based health care. The same pattern is evident when comparing children from families with incomes below 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level to children from families with higher incomes.

Nearly one in four (24%) adolescents with correctable refractive error has inadequate correction.

The odds of having inadequately corrected refractive error are significantly higher for Mexican American and non-Hispanic black youth, regardless of family income level; more than a third of Mexican American and non-Hispanic black adolescents have inadequately corrected refractive error.

An estimated 6 percent of children with special health care needs (CSHCN) have unmet vision care needs.

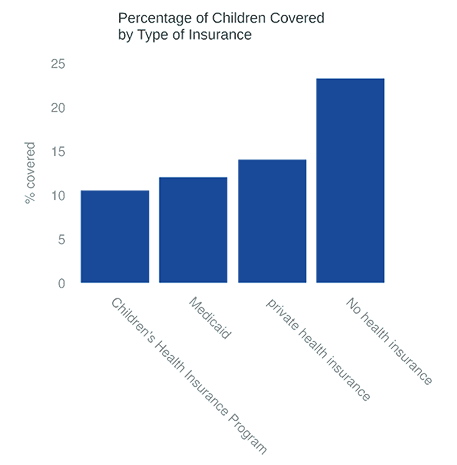

Howeve, rates differ significantly across racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups. Compared to non-Hispanic white CSHCN, non-Hispanic black, multiracial, and Hispanic CSHCN are two to three times more likely to have unmet vision care needs. CSHCN with no health insurance are almost twice as likely than CSHCN with private health insurance to have unmet vision care needs, while those Medicaid or SCHIP are less likely than those with private insurance to have unmet needs. For 13 percent of CSHCN, an adult in the family had stopped working in order to care for the child; those children are about 1.5 times as likely to have unmet vision care needs.

In a study of 5th-graders who wore eyeglasses or had been told that they needed to wear eyeglasses, 14 percent had gone without needed new or replacement eyeglasses within the last year because their parents could not afford the cost. Children from families with lower incomes and children who lacked health insurance were more likely to have gone without needed eyeglasses. Even among children covered by health insurance (public or private), only 15 percent reported having vision benefits that covered eye exams and eyeglasses.

Nationally, only one-quarter of employees of private sector businesses have access to vision benefits through their employers.

The role of health insurance in families’ ability to access vision services was significantly strengthened by the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Pediatric vision care is an Essential Health Benefit under the ACA. All new individual and small group health insurance plans, including plans sold through the Health Insurance Marketplace created under the ACA, provide coverage of vision services for children younger than 19 years. In most states, this coverage amounts to a yearly comprehensive eye exam and eyeglasses, though benefits vary by state. (See Pediatric Vision Benefits Available Under the Affordable Care Act.) In addition, all Marketplace plans cover vision screening by the primary care provider with no copay or coinsurance.

Pediatric Vision Benefits Available Under the Affordable Care Act

Pediatric vision care is an essential health benefit under the Affordable Care Act; all new individual and small group health insurance plans, whether or not they are part of the ACA’s Health Insurance Marketplace (also called “exchanges”), must provide coverage of vision services for children younger than 19 years.